When researching the history of my family, I started from scratch. Given the capabilities of online systems, I was only able to piece together a minimal story of my ancestors’ lives. However, this changed when I connected with other researchers from my family tree. They provided a wealth of resources I never knew existed: photos, priceless heirlooms, family “lore,” and, most interestingly, first-hand accounts from these almost-mythical figures.

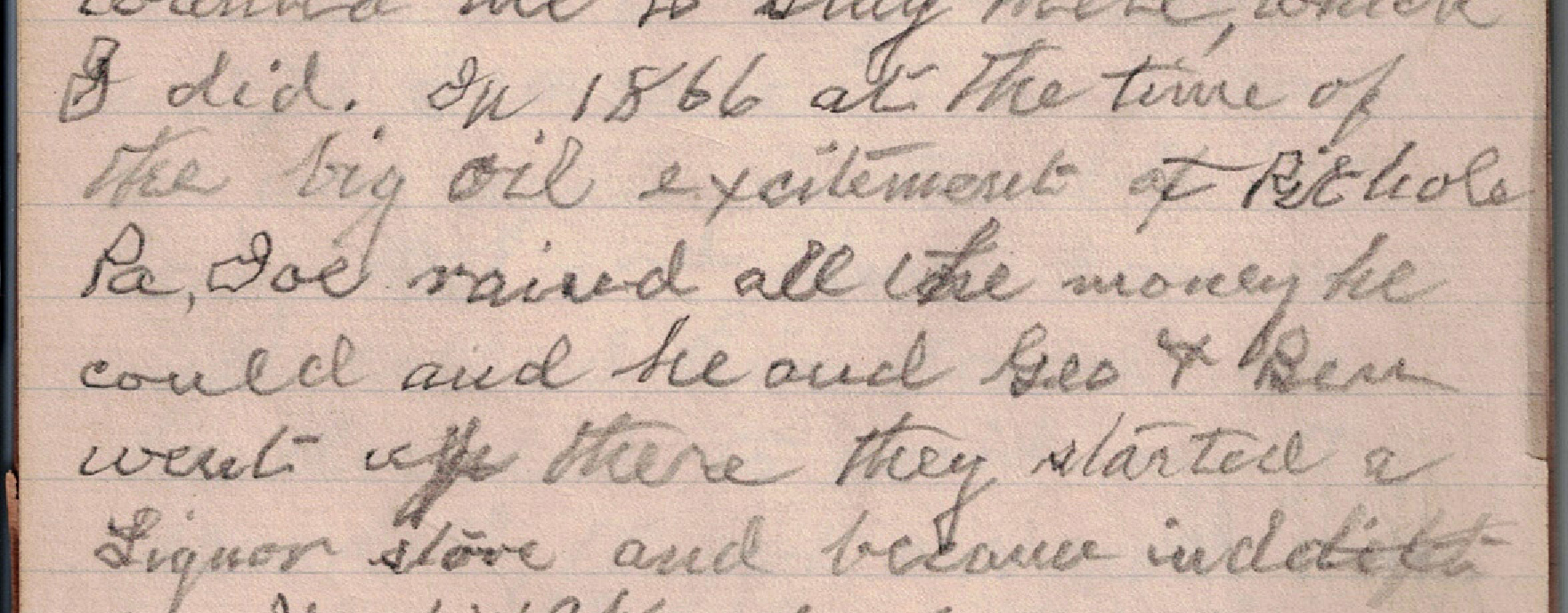

A significant discovery was the recollections of my great-great-grandfather, Edward Adam Masseth, the youngest child of Francis Xavier and Mary Ann Masseth. He played a major role in his generation’s story and recorded his experiences in a diary. The entire diary, while short, contains fascinating details, but for now I’d like to focus on one sentence that, until recently, wasn’t fully understood.

Transcription:

In 1866 at the time of the big oil excitement at Pithole PA, Joe raised all the money he could and he and Geo + Ben went up there they started a Liquor Store

For the longest time, the Masseth activities in Pithole weren’t well documented. Much of the story had been told through tales passed down through the generations, with minimal supporting evidence. Pithole was seen as a sort of backstory, where a couple of Masseth brothers spent a few years of their young adult lives before returning to New York, where their more well-known stories began. Some knowledgeable researchers may have linked Pithole to Ben’s later successes in the oil industry, but the story had never been comprehensively explored.

My goal for this post is to document as thoroughly as possible the Masseth presence in Pennsylvania throughout the 1860s, focusing primarily on their time in Pithole and providing a detailed history of Pithole itself to set the stage. I hope you enjoy it.

Origins

From the very beginning of their story in the United States, the Masseth family exhibited an adventurous spirit. The family patriarch, Francis Xavier, traveled from Alsace to New York in the 1830s, a major undertaking. His children undoubtedly inherited that same drive to pursue success, wherever it might be.

This spirit continued after his death in 1849, when his eldest son, Michael, moved to California in 1854 to participate in the Gold Rush. His second son, Ignatius, followed suit in 1859. The third son, Frank, bucked the trend and stayed in Rochester for his entire life. However, the next three children, Joseph, Benjamin, and George, went in a different direction.

Sometime before 1860, two of the three brothers moved to Canandaigua, where they stayed at the Niagara House, a local hotel. According to the 1860 census, Joseph worked as a clerk, and Ben ran the billiard room. We don’t know where George was at that time, but we do know that on April 30, 1861, he enlisted to fight in the Civil War, merely 18 days after it officially began. This kept George occupied for the next several years.

In the meantime, Joseph and Benjamin continued to work at the Niagara House. Ben had a history with the railroads, working as a bellboy for the New York Central Railroad Company as early as age 15 and later as an engineer in Ohio. It may have been through this connection, and with a little inspiration from his older brothers, that he decided to pursue his own “Gold Rush” in the hills of Pennsylvania, where a burgeoning oil industry was beginning to take shape.

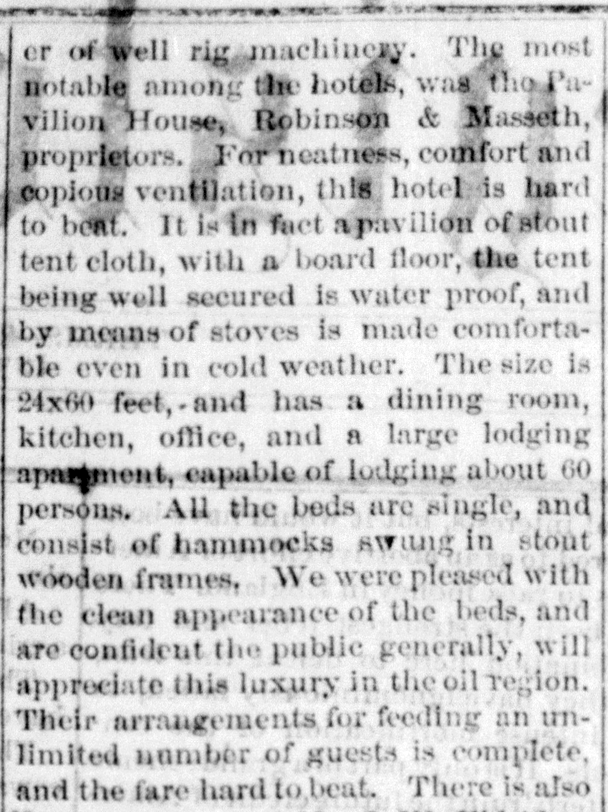

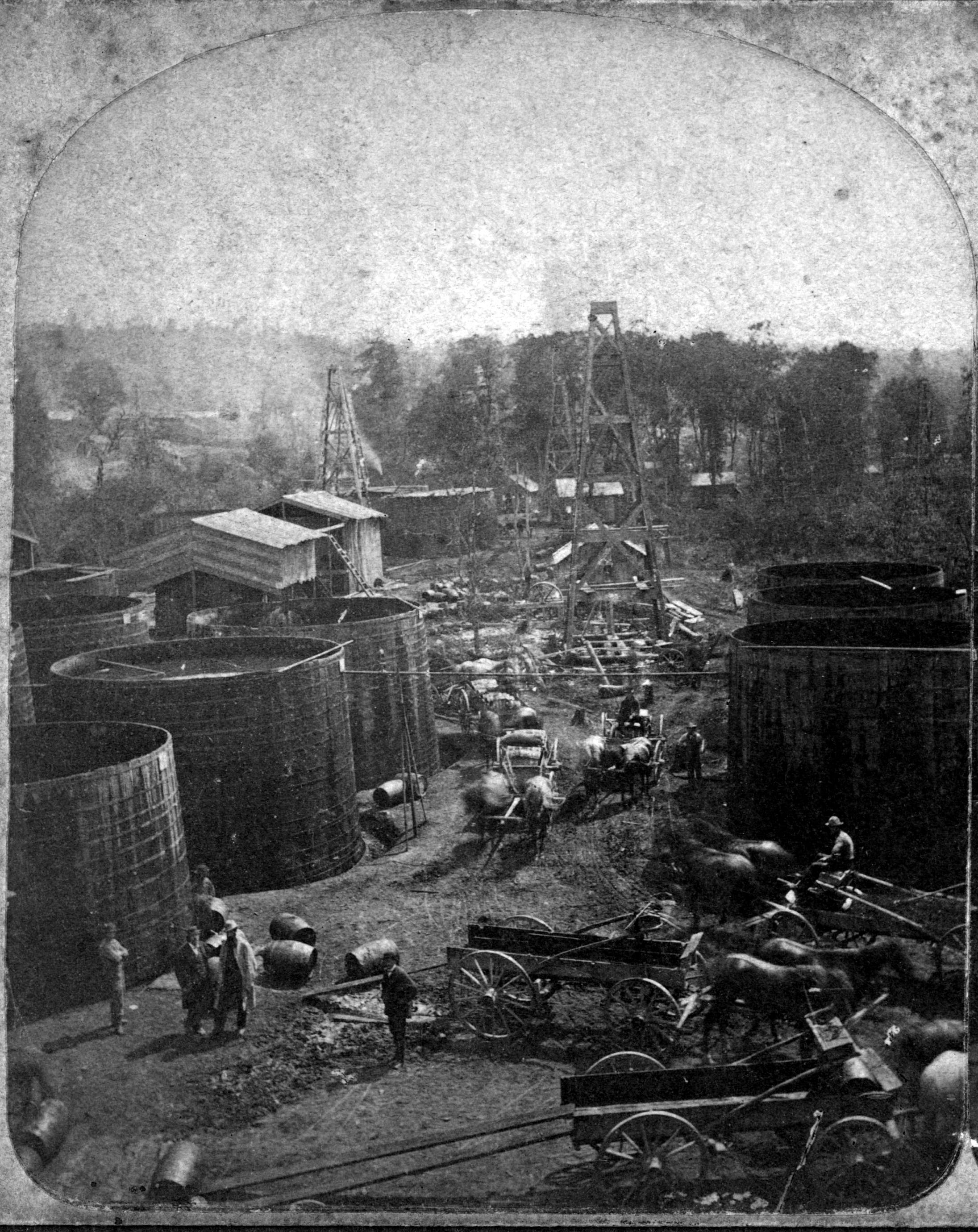

Plumer and Pithole

Ben initially settled down in a town called Plumer, located in Venango County, PA. Plumer was a small oil boomtown deep in the forests of western Pennsylvania. The history of oil can be traced back to this region, specifically back to August 1859, when Edwin Drake discovered “rock oil” (petroleum) on his property in Titusville, merely 10 miles from Plumer, igniting the Oil Rush. Plumer’s primary feature was the Humboldt Refinery, established in 1862. By the following year, it was known as one of the most advanced refineries in the region, capable of producing 1,000 barrels of kerosene per week. Ben, along with a man named John Robinson, established a hotel in Plumer alongside the founding of the refinery, calling it the “Pavilion House.” It became the preeminent hotel of the region.

In the spring of 1864, I.N. Frazier, associated with the Humboldt Refinery, along with Frederick W. Jones, J. Nelson Tappan, and James Faulkner, organized the United States Petroleum Company. In a move that many thought crazy at the time, the partners decided to drill along Pithole Creek, far from the established oil fields along Oil Creek. They leased 64 acres of land from Thomas Holmden, with Faulkner securing the lease for $1.00 and one-fourth of the oil produced, and began exploratory drilling thereafter. To determine where to drill, they reportedly enlisted the help of a diviner who used a witch hazel twig to select the drilling site. The well, dubbed the Frazier Well, was drilled in late 1864.

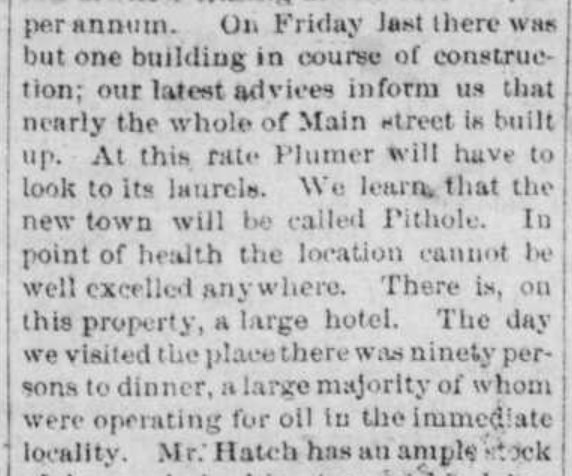

Before the Frazier Well was completed, Thomas G. Duncan and George G. Prather purchased the Holmden Farm, subject to the existing lease, for $25,000. On January 7, 1865, the well began flowing at the rate of 250 barrels per day, causing immediate excitement in the region. Almost overnight, the stock in the United States Petroleum Company surged from $6.25 to $40 per share. Within just a few months, the Frazier Well’s production increased to 1,200 barrels a day. By May, Duncan and Prather began clearing the wooded bluff above the well, laying out a town that was divided into lots and sold on May 24, 1865. It’s reported that a functional town was built-up within the following week.

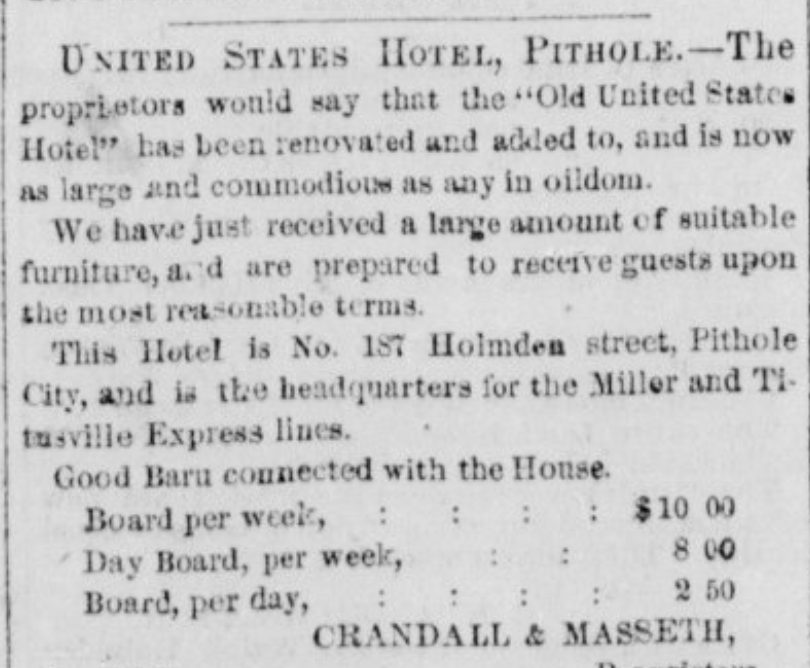

The United States Hotel

Recognizing the opportunity of the discovery of oil along nearby Pithole Creek, Ben Masseth and his partner John Robinson didn’t waste time. As the United States Petroleum Company began its drilling efforts, it constructed several buildings for storing equipment and housing workers. After the establishment of the town, one of these buildings was purchased and repurposed into a hotel, which was dubbed the United States Hotel, named after the oil company. Ben and John became the first lessees of this hotel. Their experience from running the Pavilion House in Plumer allowed them to quickly take advantage of this new opportunity, seemingly being the first on the scene in Pithole and running the very first hotel in town.

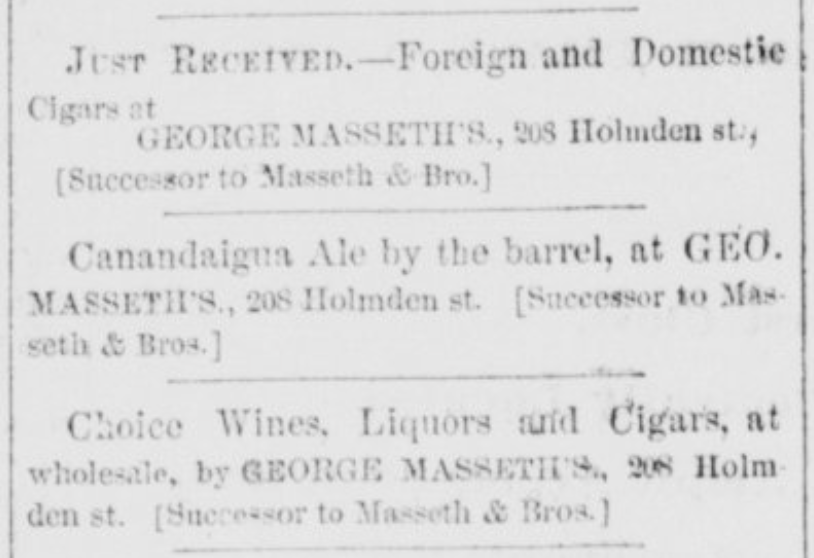

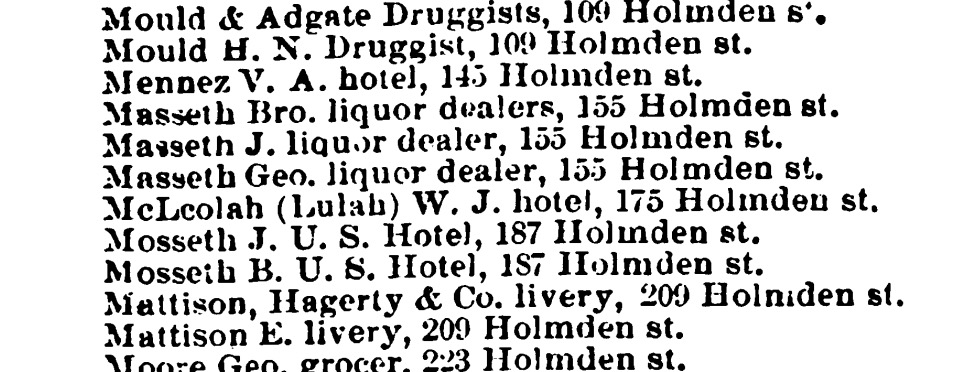

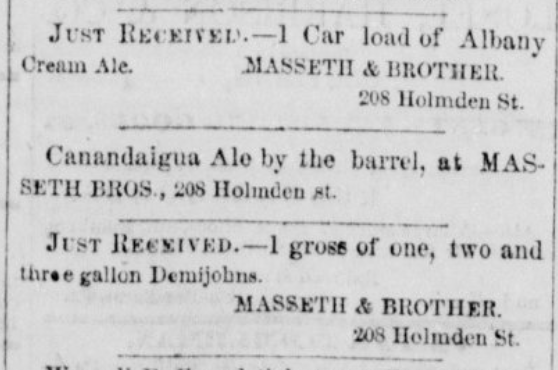

At this time, Ben’s brothers became interested in his ventures. Likely drawn by his accounts of the opportunities in the area, Joseph and George decided to join him. George, recently relieved from duty in the Civil War, arrived as early as September 1865, with Joseph probably arriving around the same time. At some point, Robinson left the hotel, leaving Ben to manage it, now joined by Joseph and new associates Merritt A. Crandall and Simeon Deyo, who helped fill the void left by Robinson. While co-managing the United States Hotel with Ben, Joseph also partnered with George to establish a liquor store called “Masseth & Brother,” advertising it in the local newspaper by December.

The Boom in Pithole

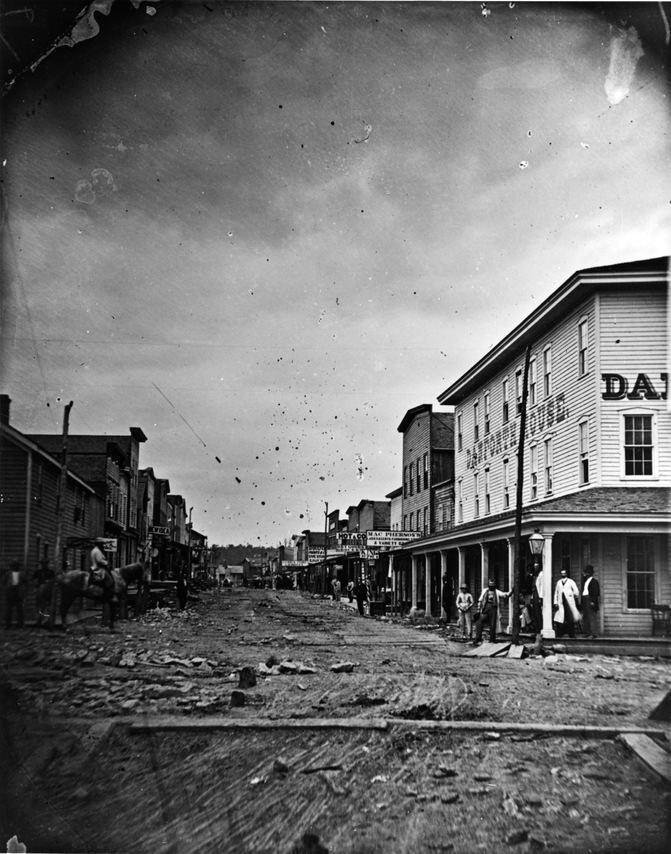

During this time, Pithole experienced its greatest period of growth. By the end of 1865, its population had exploded, making it one of the larger towns in the state. Some estimates put the peak at 20,000 residents, making it the third-largest city in Pennsylvania, surpassed only by Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. At its height, there were at least fifty hotels in the town, alongside numerous saloons, shops, and other businesses.

Many of the town’s residents were former soldiers, both Union and Confederate, who were eager to invest their savings or find work in the booming oil industry after the end of the Civil War. Pithole became the economic hub of the oil region, with reports indicating that it wasn’t uncommon for a million dollars to change hands in a single day. The demand was so intense that half-acre lots were selling for as much as $3,000, and the price of a lot lease climbed from $275 a year to as much as $850.

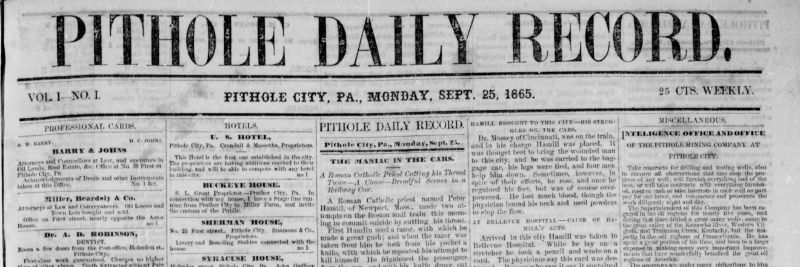

Substantial investments were made in its infrastructure. By July, a post office had been opened, which soon became the third busiest in Pennsylvania. In September, Pithole began publishing its own daily newspaper, the Pithole Daily Record. In November, the first oil pipeline in the region (arguably the first in the whole world) was completed by the Pennsylvania Tubing Transportation Company, connecting Pithole to the Miller Farm about five miles away, facilitating the transportation of oil to storage tanks and further distribution via rail.

This rapid growth, however, brought significant challenges. Water was scarce due to the town’s hilltop location and the rock strata just below the surface, making it difficult to supply the town. Pure water became a luxury, with the only supply being the infrequent “water wagons,” selling it at a dollar per barrel. It wasn’t until November that a permanent reservoir and piping system was constructed. Another issue was the pervasive mud caused by the region’s wet weather. The streets and sidewalks often consisted of a deep layer of mud. Plank sidewalks were installed to alleviate the problem, but they often sank so far below the surface that “more than ordinary length of limb was required to reach it.” This issue was eventually addressed by developing advanced dredging machines and more comprehensive plank roads. By the end of 1865, Pithole was beginning to solve most of its growing pains and was on its way to becoming a first-class city.

The Masseth Brothers in Pithole

Amidst the town’s legendary growth, the Masseth brothers managed to carve out their own niche. Ben and Joseph continued to oversee the United States Hotel, which had become one of the most prominent establishments in Pithole. The hotel catered to oilmen, speculators, and travelers who flocked to the town in search of fortune. Within a month of its founding, the hotel catered to “one-hundred and fifty guests daily.”

However, hotel competition in Pithole was fierce, and in the latter half of 1865, “no less than fifty 50” hotels were erected, and “each one was doing a lively business.” This would have put pressure on Ben and Joseph to compete.

In fact, in the very first published Pithole Daily Record issue, on September 25, The United States Hotel advertisement states that “The proprietors are having additions erected to their building, and will be able to compete with any hotel in this city.” Clearly by this point, less than four months after establishing their hotel, they were beginning to feel the pressure.

These advertisements remained unchanged for the rest of the year, so clearly these renovations were taking quite a long time. However, on January 19, 1866, it finally changed, indicating that the renovations were complete.

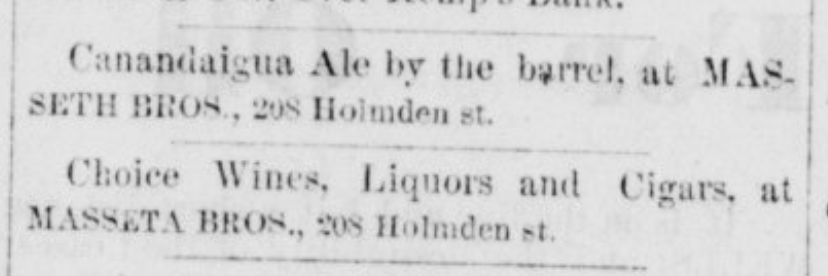

In the meantime, Joseph and George dedicated themselves to the liquor store, located conveniently close to the hotel. Their establishment became a popular spot. Featured prominently in the local newspaper, they advertised their surplus of “Canandaigua Ale,” “Albany Cream Ale,” and “Choice wines, liquors, and cigars.”

As Pithole thrived, so did the brothers. But the town’s success was fleeting, and it soon became clear that the brothers’ prosperity would not last, as Pithole’s infamous decline loomed on the horizon

The Decline of Pithole

The downfall of Pithole has been written about countless times, making it a sort of “poster child” for boom-and-bust towns. Contemporary writings tended to downplay the condition of the city, saying that “the glory of Pithole has not departed” and that “this great oily heart still continues to pulsate,” but with the benefit of hindsight, the end clearly seemed inevitable.

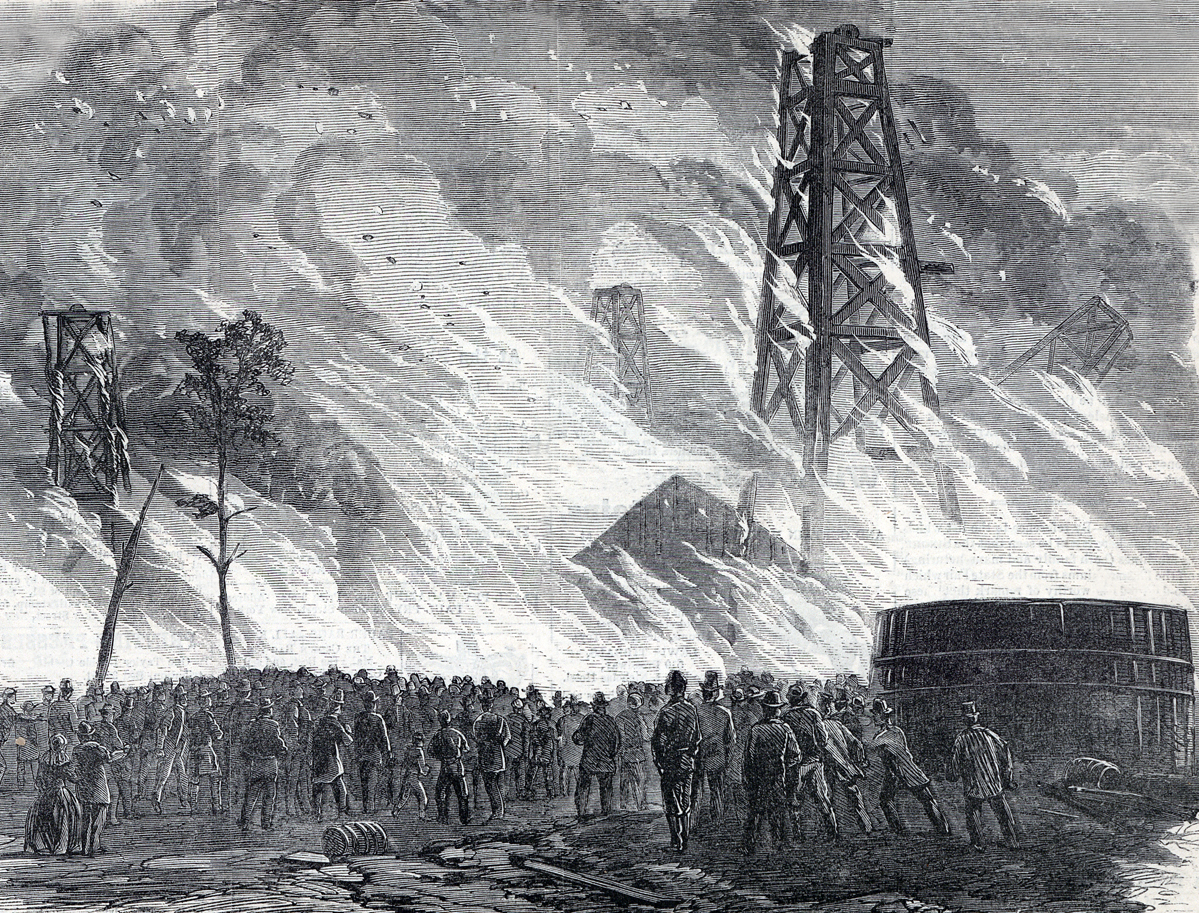

By the end of 1865, Pithole had solved many of its infrastructure problems and was able to scale up to meet the demands of its growing populace. However, there was one ever-present force that seemed impossible to avoid: fires. Due to hasty construction, all buildings were made of wood, with reportedly “not a brick or stone house in it.” This, combined with the ubiquitous presence of combustible oil and gas, turned the town into a tinderbox.

Fires were frequent and destructive. In October 1865, the Grant Well, the most famous well in the region and arguably the well that put Pithole “on the map,” caught fire. Several thousand barrels burned, and the well itself kept flowing, continuously adding to the inferno. It took several days before the fire was extinguished, during which time people congregated around the blaze. An eyewitness account says, “A painter’s skill could scarce portray the beautiful scene which this well presented while burning.” The damage was reportedly about $1,500,000, but the United States Petroleum Company was able to salvage the well for future use.

Fires were not only confined to the oil fields. The town itself burned with horrific regularity. In the months following the Grant Well fire, the frequency of fires increased. A hotel burned down in December. On February 8, three hotels were destroyed, and the United States Hotel heavily damaged. April was especially bad, with six major fires recorded during the month, destroying over 50 structures and causing an unimaginable amount of damage to oil wells in the vicinity.

Beyond the ever-present threat of fires, Pithole’s decline was fueled by a combination of economic and logistical factors. The initial oil boom was built on a foundation of speculation and overinflated expectations. People poured money into oil leases at inflated prices, turning the region into an expensive “land of derricks.” As the wells inevitably emptied, oil production declined, and new, more promising fields were discovered elsewhere. All these factors spelled disaster for Pithole.

The Brothers’ Exit

With Pithole’s downfall came the end of the Masseth brothers’ time there. A fire on February 8 severely damaged the hotel. However, it’s likely that by this point, the hotel was already beginning to fail. The town’s population was dwindling, and there was a glut of more desirable hotels nearby. The fire may have simply proved to be the final blow that caused both Joseph and Ben to abandon their venture.

Facing mounting debts from the substantial loans he had taken to finance his and his brothers’ endeavors, Joseph found himself in a precarious position. In March 1866, the liquor store was rebranded as “Geo Masseth’s,” likely signaling Joseph’s departure from the venture. By May 1866, Joseph had returned to Canandaigua, bankrupt.

The final advertisement for the United States Hotel appeared in April 1866, and the liquor store’s last appeared the following month, marking the end of the Masseth businesses in Pithole.

After Joseph returned to Canandaigua, he was helped out by his brother Frank, and eventually, together with his other brother Edward, financially recovered enough to start a new hotel in Canandaigua, where he would finally find success.

Ben, ever the entrepreneur, remained in the Pithole area and pivoted to a new career in the oil industry by manufacturing “fishing tools,” devices used to retrieve drilling equipment from oil wells, which were essential as drilling activity continued in the region. He later used this knowledge, along with a partnership with inventor William Downing, to invent several useful devices and improve existing technologies. He gained renown for these innovations, particularly the casing cutter and well packer, inventions that earned him a considerable fortune after he moved to nearby Butler in the following decade.

George, despite these setbacks, chose to stay in Pithole a while longer. His activities during this period were less visible, but we know of his passion for sport. Newspaper articles of the time detail his success at billiards, noting his impressive “large runs” and his victory in the Venango County Billiards Championship. He also appeared in box scores throughout 1866, highlighting his participation in an early form of “base-ball.” Additionally, George engaged in local governance, serving as Borough Collector for 1867. That is the last mention of George in Pennsylvania, as the following year he moved back to Rochester, where he would spend the rest of his life making a name for himself as a well-known hackman and undertaker.

Conclusion

The story of the Masseth brothers in Pithole is one of ambition and resilience, set against the backdrop of a short-lived boomtown. They seized opportunities where others might have hesitated, making their mark during Pithole’s rise. But like the town, their success was brief, fading as Pithole quickly declined. Despite the setbacks, the brothers’ determination stayed strong. Each found ways to rebuild, carrying the lessons of Pithole into the next chapter of their lives.